Prisoners of war interned in Switzerland

At the suggestion of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Swiss government, Germany, France, Britain, Russia and Belgium signed an agreement in 1914 regarding prisoners of war (PoWs). The agreement stated that captured military and naval personnel who were too seriously wounded or sick to be able to continue in military service could be repatriated through Switzerland, with the assistance of the Swiss Red Cross. The first repatriations were made in March 1915, and by November 1916 some 8,700 French and 2,300 German soldiers had been repatriated.

The next step was the internment in Switzerland of PoWs who, though sick or badly wounded, might still be capable of military work away from the front line, and could therefore make fit soldiers available for serving at the frontline if they were repatriated. Internment in Switzerland would aid their recovery without furthering the enemy’s war effort. At the suggestion of the ICRC, a reciprocal agreement was signed between Germany and France. The UK and Belgium signed agreements with Germany slightly later. Travelling commissions of Swiss doctors visited PoW camps to select potential internees. Once a PoW had been selected, he would be brought before a board comprising two Swiss Army doctors, two doctors from the country holding him captive, and a representative of the prisoner’s own nation.

The next step was the internment in Switzerland of PoWs who, though sick or badly wounded, might still be capable of military work away from the front line, and could therefore make fit soldiers available for serving at the frontline if they were repatriated. Internment in Switzerland would aid their recovery without furthering the enemy’s war effort. At the suggestion of the ICRC, a reciprocal agreement was signed between Germany and France. The UK and Belgium signed agreements with Germany slightly later. Travelling commissions of Swiss doctors visited PoW camps to select potential internees. Once a PoW had been selected, he would be brought before a board comprising two Swiss Army doctors, two doctors from the country holding him captive, and a representative of the prisoner’s own nation.

The first of these internees, 100 German and 100 French PoWs suffering from tuberculosis, arrived in Switzerland in January 1916. By the end of 1916, nearly 27,000 former PoWs were interned there, about half of whom were French, one third German and the remainder mostly British or Belgian. As the internees entered Switzerland, and at stages along their journeys, they were often surprised to be greeted by thousands of Swiss who had turned out to welcome them (as at left).

A hotel decked out in flags to welcome British prisoners of war arriving in Switzerland from prisoner of war camps in Germany. By the end of the war, nearly 68,000 men had been brought to Switzerland for internment. Selection for internment was done on the basis of individual needs, rather than on a quota or exchange basis by nationality. Some civilians were also interned, presumably men who were of military age who had been detained in enemy countries.

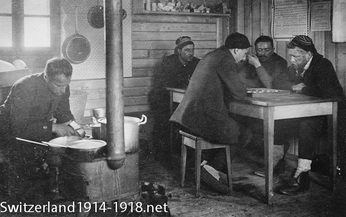

British and French prisoners of war with Swiss people at a meal to welcome them to Switzerland.

Internees were held or worked at a number of locations. For the British, the main camps were in south-western Switzerland, east of Lake Geneva. One of the main centres for interned British was in the vicinity of Châteux d’OEx. The first interned British ex-PoWs to reach Switzerland, about 300 officers and other ranks, arrived there on 31 May 1916. Some 700 British internees were eventually held in the vicinity. Leysin was used for British tuberculosis sufferers.

Internees were held or worked at a number of locations. For the British, the main camps were in south-western Switzerland, east of Lake Geneva. One of the main centres for interned British was in the vicinity of Châteux d’OEx. The first interned British ex-PoWs to reach Switzerland, about 300 officers and other ranks, arrived there on 31 May 1916. Some 700 British internees were eventually held in the vicinity. Leysin was used for British tuberculosis sufferers.

Image: Indian and Gurkha troops amongst the British Imperial soldiers interned at Chateaux d'OEx. They are at an event to celebrate their arrival in Switzerland.

Click here to find out more about how the British Red Cross helped the British PoWs at Châteux d’OEx.

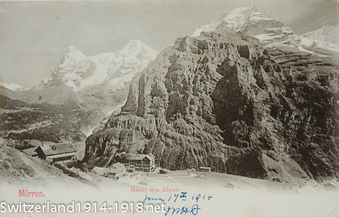

Another camp for British internees was at Mürren, which held 600 men and 30-40 officers. This village was built on a ledge high up a mountain, and for seven months each year was virtually cut off due to snow. Although the view was beautiful, many of the internees were so badly ill or wounded that they were confined to their billets when it snowed. This postcard (sent home by a British visitor just before the outbreak of war) shows the difficult terrain around the tourist resort at Mürren.

Image: German troops interned in Switzerland, who have formed an orchestra to pass the time. Life for the internees was not necessarily easy. They were still under military discipline, enforced by the Swiss commandant of their camp. Regular roll calls were held, and if a man was found to be missing without permission, for example, he might be briefly imprisoned on his return. Some German internees were said to have preferred the English PoW camps to the Swiss internment camps!

Image: German troops interned in Switzerland, doing woodwork in their workshop. Items made by internees were sometimes sold to raise money to contribute towards their care.

A small number of Austro-Hungarians were also interned, but apparently no Russians. No Americans were interned, because the US and Germany only signed an agreement on this issue on 11 November 1918.

A small number of Austro-Hungarians were also interned, but apparently no Russians. No Americans were interned, because the US and Germany only signed an agreement on this issue on 11 November 1918.

Image: British PoWs interned in Switzerland. A British

report compiled in late 1917 found that some camps were not in places suitable

for wounded men to recover, that there were insufficient medical staff, and

that artificial limbs were not available for men who needed them. This photograph perhaps conveys another problem: the risk of serious boredom, often added to existing psychological effects of having been a prisoner of war for several years.

If their wounds or illness permitted, interned other ranks were expected to work. These (left) are French internees doing farm work. Depending on the long-term effects of wounds or illness, this work could range from working for a private Swiss firm in the internee’s pre-war profession, to learning a new trade which would be useful after the war, if the internee could no longer follow his old one.

According to 'The Times History of the War' this photo was taken at Brienz.

According to 'The Times History of the War' this photo was taken at Brienz.

The terms under which internment occurred changed over the course of the war, as individual countries made bilateral agreements. Under a May 1917 agreement between France and Germany, internees were automatically repatriated to their home country after being in captivity for more than eighteen months, if over a specified age. An Anglo-German agreement in mid-1917 broadened the terms of eligibility for internment to men who had spent at least 18 months in captivity and who were recognised as suffering from so-called “barbed wire disease”, meaning the mental strain of being held prisoner. It was also agreed at this time that internees whose recovery was likely to be prolonged would be repatriated. One internee who was repatriated in 1917 due to wounds suffered was Arthur Whitten Brown, who made the first trans-Atlantic crossing by air in 1919. Although in theory repatriated ex-PoWs were meant to be no longer fit for military service, on his return to the UK he seems to have worked as a flying instructor!

Not all internees left Switzerland at the end of the war. By 1923, a British war cemetery had been constructed at Vevey, on the north-east shore of Lake Geneva. This holds 88 British graves, mostly those of internees who had succumbed to their wounds or had died in the influenza epidemic (click here for more information on this cemetery from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website).

The agreements mentioned above were the most frequent way that troops of the belligerent states came to be interned in Switzerland. However there was another way. Any soldiers who crossed the frontier into Switzerland, whether deliberately or accidentally, would be disarmed and interned. One example was the crews of a number of aircraft that landed (or crash-landed) in Switzerland.

Not all internees left Switzerland at the end of the war. By 1923, a British war cemetery had been constructed at Vevey, on the north-east shore of Lake Geneva. This holds 88 British graves, mostly those of internees who had succumbed to their wounds or had died in the influenza epidemic (click here for more information on this cemetery from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website).

The agreements mentioned above were the most frequent way that troops of the belligerent states came to be interned in Switzerland. However there was another way. Any soldiers who crossed the frontier into Switzerland, whether deliberately or accidentally, would be disarmed and interned. One example was the crews of a number of aircraft that landed (or crash-landed) in Switzerland.

See the excellent website hopitauxmilitairesguerre1418.overblog.com for lists of locations where prisoners of war were interned in Switzerland.

Below: a slideshow of further images of soldiers interned in Switzerland during the First World War: